Data consistency: the problem (1/3)

We base (or should) decisions on the data we store in user interaction with our product. We save all the information necessary to provide answers and develop predictions based on historical data, adapting and anticipating the needs of our users.

Have you ever wondered if this data is consistent?

In this post, we will discuss consistency: what it consists of and how it has evolved throughout different architectures, influences, and technologies.

We interpret that our data is consistent if:

The data relates correctly without generating inconsistencies, with referential integrity.

Valid and concrete states are maintained (the number of units of a product for an order matches the stock output record).

They are available for reading once the transaction (action or operation on the database) is completed.

Relational database management systems or RDBMS (SQL Server, Oracle, MariaDB, MySQL, etc.) guarantee the consistency of the stored data through ACID in their transactions:

Atomicy: The transaction is executed completely, or not at all.

Consistency: It will only execute the transaction if it respects the referential integrity guidelines and defined rules, maintaining valid and exact states at all times.

Isolated: A transaction cannot affect another, guaranteeing that the final state of concurrent executions will be the same as those executed sequentially through concurrency control.

Durability: Guarantees the persistence of the data once the transaction has been executed, even if the system fails.

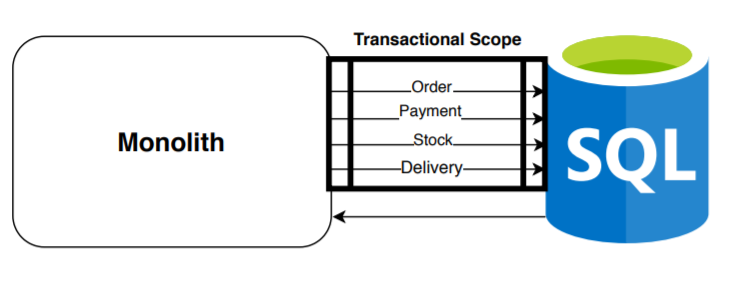

The main and initial high-level architecture, the most common, widespread, and that we all know:

We have a main component that manages the transactions carried out on a single database for each use case of the application. As you can see in this example, we execute a transaction (including in it all the operations necessary to correctly complete a new order). Indeed, the relational database guarantees us ACID, offering us consistency in the creation of the entire order, but very poor results in terms of efficiency, scalability, and availability when handling large amounts of data.

In 1998, Carlos Strozzi introduced the concept of NoSQL for his open-source relational database, since it does not use SQL as a query interface. Eric Evans and Johan Oskarsson (last.fm) reintroduced the concept NoSQL/NoREL referring to non-relational databases (denormalization or destructuring of data giving better efficiency).

Companies like Twitter, Facebook, Amazon, and Google lead the adoption of non-relational databases given the need for more efficient processing of large volumes of information in a distributed data cluster, thus allowing horizontal scaling. The Big Data concept is official in 2005.

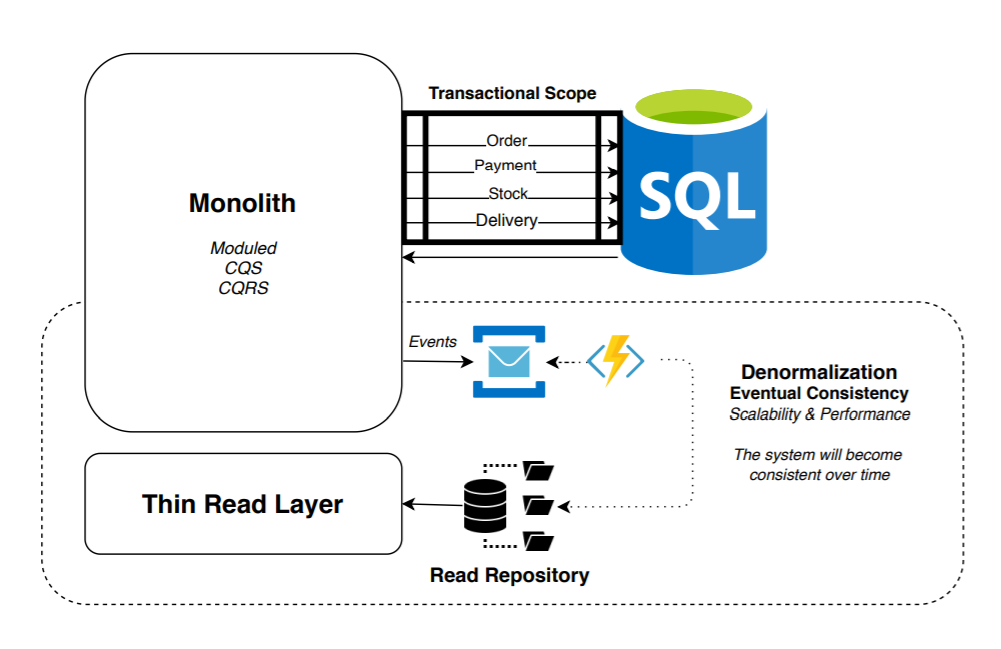

We begin to evolve the architectures. One of the most common next steps was the following:

New NoSQL databases (Apache Solr, ElasticSearch, Redis, etc.) begin to be integrated, increasing the query speed exponentially. We synchronize and transform the data (projecting and denormalizing it) from the relational write database to the non-relational read database through events incrementally (once the changes occur) or even through change control strategies in the relational database.

Back in 2011, I shared my experience with the implementation of Apache Solr: /getting-started-apache-solr/

In this scenario, responsibilities begin to be divided, modularizing the monolith and beginning to separate the read and write models. Patterns like CQS or CQRS begin to be relevant.

The consistency of the data between both databases is done eventually (there is a delay in the recovery of the data): although always maintaining a data source (source of truth) reliable that guarantees ACID in its write transactions (we could perform at any specific time a repair of certain incongruous data that may exist in the reading repository).

In this context and having a balanced solution, we begin to be aware of the complexity and adjacent coupling caused by having a single component (monolith) generating a large number of deficiencies in the quality of the code, modularity, maintainability, and scalability of the infrastructure.

In 2003, Eric Evans publishes Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software, providing a strategic vision of domain division through subdomains and bounded contexts. As well as communication techniques between bounded contexts according to their types of collaboration: context mappings.

I leave you here a series of posts that I wrote in the reading of Implementing Domain Driven Design by Vaughn Vernon: /implementing-domain-driven-design-book-vaughn-vernon/

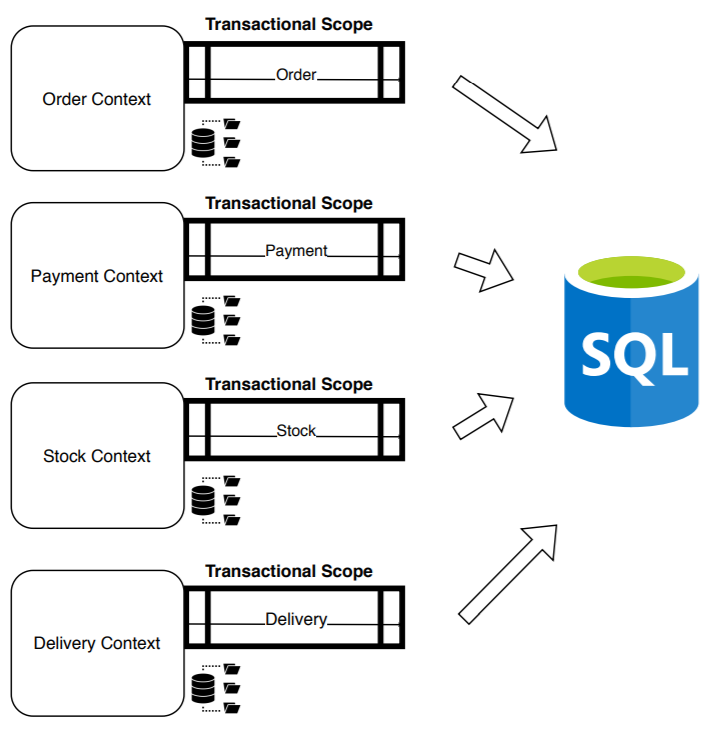

Recognizing the advantages and suffering the disadvantages, we begin to take steps to the following types of architectures with the objective of dividing the monolith, creating non-relational read databases per service, dividing the responsibilities and adapting the synchronization processes from the transactional database.

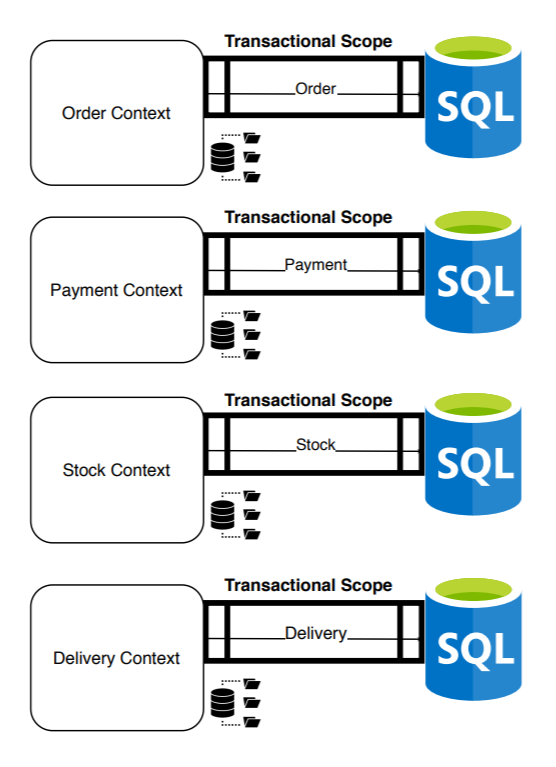

With the objective of completely decoupling the contexts and avoiding dependencies, we needed to divide the database: a transactional database per context:

At this moment, we have a distributed system increasing flexibility, scalability, and availability. Although, we have divided the transactional scope in the creation of the order. Now, we only guarantee ACID in each of the individual transactions and not in the total creation of the order: we have solved countless problems paying with the currency of consistency. From this moment on, creating an order will become a distributed transaction.

The numbers and data begin to be incongruous: How can there be less stock than what the reports reflect? How is it possible that there is a payment and not the refund if the order was canceled? How can we have an order sent without the associated stock output? etc.

Let’s remember the CAP Theorem (presented by Eric Brewer in 2000) in which he explains that in a distributed system it is impossible to simultaneously guarantee more than two of the following characteristics: Consistency, Availability (receives a non-erroneous response but without guarantees that consistent data is recovered) and Partition Tolerance (the system continues to function even if some of its nodes fail).

Eric Brewer specifies the characteristics of distributed systems (based on his theorem and excluding consistency) to BASE (Basically Available, Soft state and Eventual consistency).

At that time, following the dynamic leaning towards Partition Tolerance & Availability and neglecting the consistency of the data and other factors (essential complexity vs accidental complexity), we continue to increase our distributed system.

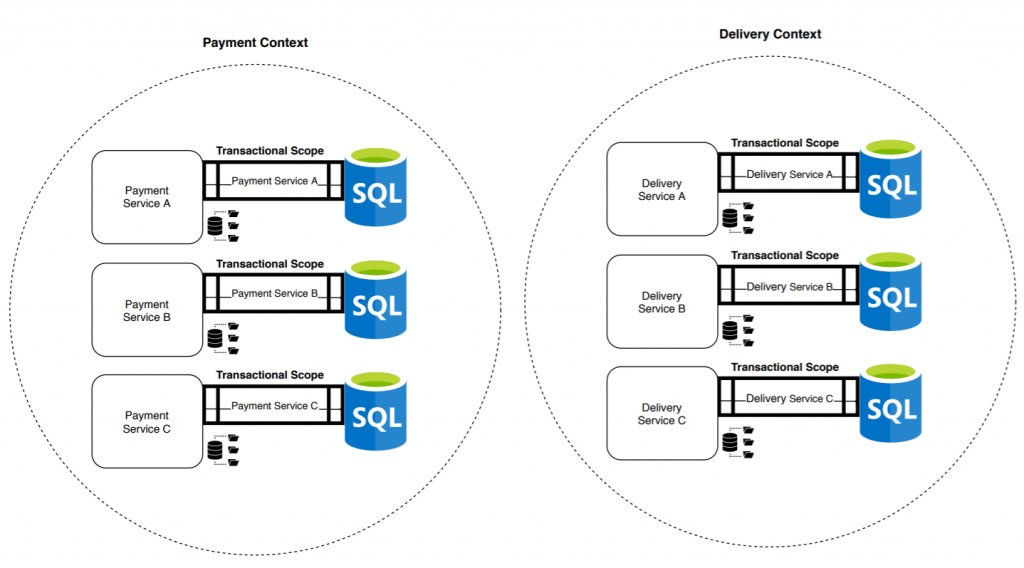

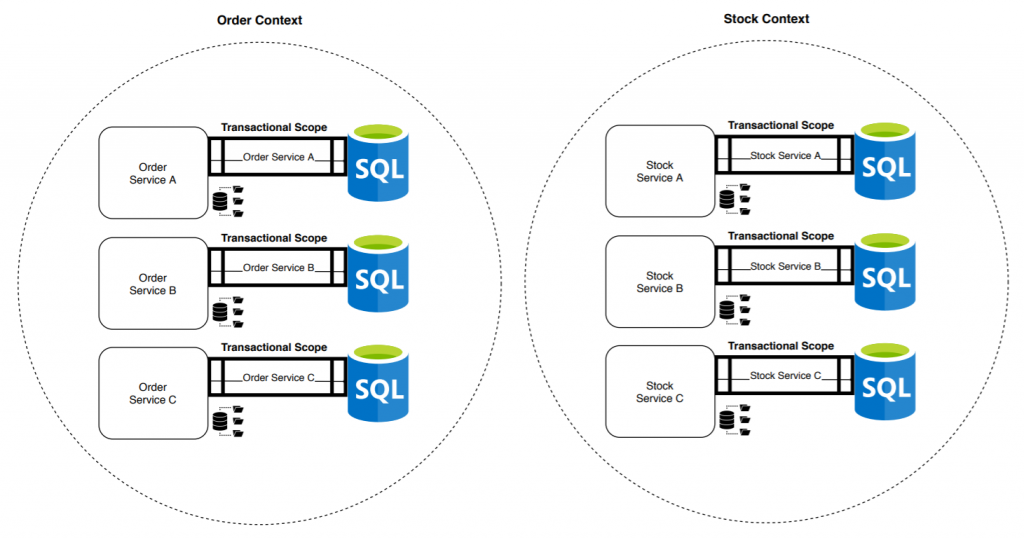

Sam Newman publishes Building Microservices in 2014 becoming a reference book in the community. Promoting the dynamics of division and evolving our architectures towards microservices:

The bounded context becomes a cohesive grouping of microservices. Now we no longer have a single transaction that guarantees ACID, nor four, but twelve: one per microservice. The risk of data inconsistencies increases, as well as the demand for knowledge necessary to face the problems generated by this type of system.

My main intention in this post was to raise and summarize the current problem in data consistency over time. Since it seems that we do not pay enough attention to the problem and neglect practices that help us, at least, to mitigate it. After all, technology is at the service of the product and the improvement of the product (among other aspects), of the data it generates.

It is true that I have not detailed the great advantages that dividing responsibilities has entailed (I leave it for another post), which are many and varied. And these advantages are what always declined the balance of our decisions until we have the distributed systems that we usually have today. Although from time to time, we must try to balance it. Or at least, be aware of what we have left along the way through critical thinking.

In the next posts I will share different patterns that will help us to correctly manage distributed transactions, thus generating a more consistent system without sacrificing Availability and Partition Tolerance (Outbox Pattern and Sagas) and we will see other possibilities avoiding working with two repositories simultaneously.